Getty Images/SuperRare:

Everyone knows the real estate market is insane these days, but most folks have no idea there is another land rush happening right now where prices have shot up more than 3,000% in just the past six months.

The problem? These pricey places don’t actually exist—at least not in the physical world.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, demand for plots of land in virtual worlds, called metaverses, has been been soaring.

The various augmented reality platforms hosting these deals are modern-day iterations of popular online experiential platforms from the early internet, like The Sims or more recently Second Life. But now there’s a difference: These virtual worlds are built on encrypted blockchains, typically with their own cryptocurrencies. So in addition to being able to craft new, alternative identities, make friends, display digital artwork, or have virtual affairs, you can conduct safe and—if you choose—large-scale financial transactions.

And people are taking the bait.

The online real estate rush is a new kind of Wild West of the internet where speculation is rampant. Those who see the potential of these buzzy, virtual realms are spending cryptocurrency worth tens—sometimes hundreds—of thousands of dollars on virtual property. Sound familiar?

It’s an offshoot of the recent high-profile popularity of nonfungible tokens, or NFTs, in which digital files, usually artwork, are sold, sometimes for head-spinning sums. That market exploded into the public consciousness earlier this year when one digital piece sold at Christie’s for nearly $70 million.

The world of digital real estate has lately seen some startling deals as well. The ownership rights to the Mars House, a sleek but fictional glass home on the red planet designed by artist Krista Kim, went for more than $500,000 in March. For comparison, the median list price of a home in the real world was $380,000 in May, according to Realtor.com® data.

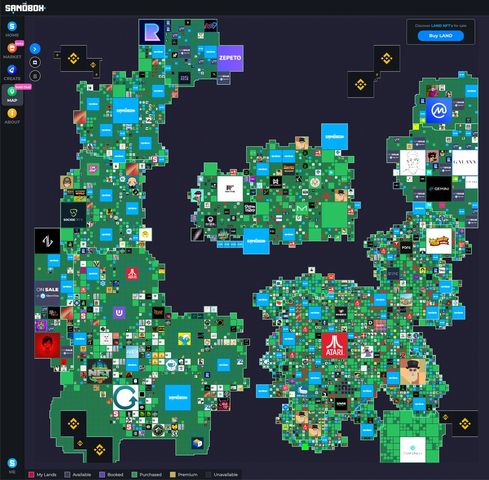

Depending on whom you ask, the virtual real estate business could become the next big thing—or wind up the next big bust. It’s a bit like the early days of Bitcoin. Some investors are worried about missing the opportunity to buy digital property in the most popular metaverses—like Decentraland, The Sandbox, Cryptovoxels, and Somnium Space—while they still can. Gaming company Atari has its own metaverse in the works.

“It’s too soon to say if it’s madness or pure genius,” says Gauthier Zuppinger, chief operating officer and co-founder of NonFungible.com, which tracks NFT markets and analyzes data. “But there is definitely something there.”

SuperRare

The folks spending big bucks in metaverses envision a future in which young people migrate to these worlds to attend virtual concerts featuring popular real-life artists, display their NFT collections—and shop. They anticipate big brands setting up online malls. Users could conceivably wander in and purchase things like sneakers, for their avatars in the games as well as for themselves—physical pairs that can be shipped to their home addresses.

Some of this is already happening. Rapper Travis Scott held a concert in the online video game Fortnite in April 2020 as the coronavirus shuttered concert venues around the world. The show got more than 45 million views.

The trading of virtual real estate is not entirely new: Plenty of money was made trading virtual real estate during the heyday of Second Life in the previous two decades. The top end of the market was much lower, but the idea was much the same.

And most of today’s virtual real estate transactions do not involve six-figure deals. Fans of today’s cyberspaces are spending much more modest amounts on virtual land where they can create the homes of their dreams outfitted with all of the amenities they can’t afford in the real world. Users can even get mortgages, in some instances, or pay a builder to put up a “home” on their virtual properties.

About $8.6 million in real estate has been sold since April in The Sandbox, a metaverse created for gamers that is still in beta form, according to the company.

Some online worlds, like Upland and SuperWorld, have created virtual platforms based on locations in the real world. In these places, buyers can purchase fictional versions of actual existing real estate, like the Empire State Building.

“This just represents the next iteration of the internet,” says Michael Gord, CEO and co-founder of Global Digital Assets Group. His Canadian-based company is just like a typical real estate developer—except online. His company buys up real estate in public metaverses with the intention of creating malls in the business districts of these worlds with storefronts that can eventually be rented out to real-world brands. He intends to eventually launch a real estate investment trust for investors.

“We’re at the very beginning of it,” he says.

Why are investors betting big on digital land?

Courtesy of Decentraland

While metaverses are by no means mainstream, investors are betting that will change as they attract a critical mass of younger players. Once they develop a strong user base, the theory goes, they’ll become more attractive to advertisers who have the money to open virtual stores or entrepreneurs who can create just about anything they can conceive of as they aren’t limited by pesky little things like zoning boards—or, you know, gravity.

Land is valuable in these worlds because, while the internet may be infinite, metaverses are not. Most are designed to have only a set amount of land, so more can’t be added at a later date.

All of Decentraland’s 90,000 parcels of land, each measuring 52 virtual feet by 52 virtual feet, or about 2,704 square feet, were sold in auctions in 2017 and 2018. But buyers can find them for sale on marketplaces, where the most expensive assemblage as of May 21 was listed at 10 trillion MANA. That was equal to nearly $8.7 trillion as of June 2. There were plenty listed for hundreds of thousands of dollars each, while the cheapest parcel was listed at the equivalent of $3,429.

“It creates the perception of scarcity, which creates value,” says Janine Yorio, managing director of the Republic, a financial services company for alternative technology investments.

Just like in real life, location also matters. A place where people congregate virtually, such as a nightclub district, casino, or sports stadium, will be more valuable to brands than the more remote outskirts of a metaverse where folks rarely venture.

But there’s no way of knowing who is buying what, and if they’re big-time investors or simply fans of the games, at this point. All transactions are recorded anonymously on the blockchain these worlds use.

In Decentraland, buyers have ranged from brands, communities, and individuals, says Dave Carr, a spokesman for the Decentraland Foundation.

“If you’re a brand and you’re trying to reach Generation Z and the millennials, then being in a virtual world where there’s lots of people that are notoriously hard to reach spending hours in these games each day, it makes a lot of sense,” says Jason Dorsey, president of the Center for Generational Kinetics, a Gen Z and millennial research firm based in Austin, TX. “You want to be where Gen Z is, and where Gen Z is right now is in these games.”

“People and companies are testing what they can do,” says Zuppinger of NonFungible.com. “There is no geographical limitation. You can interact with almost anyone in the world.”

Younger generations are likely to drive the virtual land rush

Courtesy of The Sandbox

While spending this kind of money online may be mind-boggling for nondigital natives, these worlds are often second nature for the younger generations, such as Gen Z, whose oldest members are around 24 now.

“We’ve never known a world without technology,” says Jonah Stillman, a member of this generation. He’s the co-founder, with his father, of GenZ Guru, a generational consultancy group. “The real world and the virtual world have always overlapped for us.”

Of course that overlap exists today for older generations as well, whether ordering household staples online or streaming their favorite movies to their real-world TV sets.

But the growth of metaverses suggests that the borders between real and virtual are disappearing faster than many might think.

“There’s been a very clear distinction between whether you were operating in the physical or digital world,” says Stillman. “That line is no longer even being blurred; it’s closer to being eliminated.”

Gen Z isn’t gobbling up large amounts of online real estate—yet. Most members don’t have the tens of thousands of dollars required to do so. But experts predict they will turn to these metaverses both as places to hang out, and eventually as places to invest. That’s why the real estate could become valuable for companies that are marketing to them.

“The younger generation has less faith in the traditional stock market than older generations, has less faith in the banking system and the institution of government itself,” says Dorsey of the Center for Generational Kinetics. “Many of them are more open to investing in cryptocurrencies, purchasing NFTs, and buying land in virtual worlds.”

The intersection of digital and physical real estate

Provided by Shane Dulgeroff

Eventually, there may be more of an intersection between digital and physical real estate.

Already, one enterprising real estate agent is attempting to sell the real-world duplex he owns in Thousand Oaks, CA, coupled with an animated NFT rendering of the property.

In April, Shane Dulgeroff put the home and the NFT up for sale on OpenSea, an online marketplace for NFTs and other digital assets. The asking price is about $1.4 million worth of the cryptocurrency Ethereum.

“It went very viral,” says Dulgeroff, an agent with Beverly & Co. in Westlake, CA. “I wanted to pioneer the space.”

The duplex he owns generates about $60,000 annually in rent, according to Dulgeroff’s website. It’s also permitted for a third unit in the predominantly single-family neighborhood where it’s located. The NFT was created by artist Kii Arens.

Dulgeroff received an offer equivalent to about $1.1 million, but decided to hold out for a better one. At one point he put the property on the multiple listing service to attract more potential buyers, but pulled it off when the offers didn’t come in. The auction ended on June 1 without receiving any bids.

He plans to develop the third unit on the building. He anticipates attempting to auction it off again on a real estate platform that he’s developing that will use blockchain technology.

“It’s a really unique way to blend art and real estate. How it evolves is going to be very interesting,” says Dulgeroff. “It’s obviously in its infancy right now, but the technology behind NFTs has the capability to potentially change how real estate is sold.”

Not everyone is bullish on the metaverse land grab

Courtesy of Decentraland

However, there are plenty of skeptics out there who can’t understand why people are paying more for digital coordinates in a fake world than a luxury home in the real one.

Their main contention is that digital real estate isn’t tied to anything of real-world value. So if someone spends a ton of money on a virtual property in a particular metaverse, if the virtual world fades in popularity, the online real estate could become worthless. Even if a particular location becomes less desirable in the real world, its owner still holds the deed to something tangible.

Some fear this could become a virtual bubble.

“The whole definition of a bubble is when you realize there’s no underlying intrinsic value and the market is simply propped up by speculation,” warns real estate professor Mark Stapp, at Arizona State University in Tempe. “If you pop a bubble, there’s nothing there.”

Ultimately, the value of virtual land is tied to how much folks believe it’s worth.

“It’s people entertaining themselves by buying into a fad,” says Edward Castronova, an economist and media professor at Indiana University Bloomington.

“These things can eventually [fall] out of favor, and they’re useless. … Just being able to say you own an NFT is not going to sustain value,” he says.

The post Digital Land Rush Has People Spending Big Money on Imaginary Real Estate appeared first on Real Estate News & Insights | realtor.com®.