Provided by Mapping Inequality

It’s been more than a half-century since racially discriminatory real estate lending policies were outlawed. However, the effects continue to weigh on historically Black communities to this day, holding residents back from building wealth through homeownership.

Through the practice of redlining, beginning in the 1930s, communities of color were segregated and labeled as undesirable to lenders, many of whom refused to issue mortgage and home renovation loans there. Redlining was banned by the 1968 Fair Housing Act, but in 2019, homes in formerly redlined areas across the country were sold for an average 29% less than the homes in historically white communities, according to a recent realtor.com® analysis.

That’s a big deal, considering that homeownership has traditionally been a stepping stone to financial stability for Americans. The legacy of redlining, it seems, continues to penalize people of color today, leaving them with less money in the bank.

“Redlining is not just our history, but our present as well,” says David Troutt, a law professor who leads the Center for Law, Inequality and Metropolitan Equity at Rutgers University. Troutt is also the author of “The Price of Paradise: The Costs of Inequality and a Vision for a More Equitable America.”

“It’s not unusual across the country to see vast disparities among neighborhoods in the same city” as a result of redlining, Troutt says.

Location and quality of housing stock play a part in home values as well. Homes in formerly redlined areas are often smaller and were built with cheaper materials than those in historically white neighborhoods with tree-lined streets. Redlined communities also often suffer from poorer reputations and schools and have fewer amenities that would make them more attractive to buyers unless they have been gentrified.

The price differences between redlined and non-redlined communities varied greatly across the nation. However, they were the most pronounced in Alabama’s Jefferson County, which includes Birmingham. The city was notorious for its resistance to the civil rights movement, with police officers beating up peaceful protesters. It was also where members of the Ku Klux Klan bombed a Black Baptist church in 1963, killing four girls.

Homes in Jefferson County’s formerly redlined communities sold for an average 74% less than those in historically white communities, the biggest difference of any of the counties in our analysis.

“Homes in [Black] areas, even when they have the comps to support list prices and agreed-upon prices, seem to consistently come in under value,” says Marcus Brown, president of the Birmingham Realtist Association. The chapter of the National Association of Real Estate Brokers is an organization for Black real estate professionals. “You buy a home in an area, it appreciates at a much lower rate.”

Jefferson County was followed by Fulton County, GA, home to Atlanta, where there was a 67% difference in home prices; Jackson County, MO, home to Kansas City, at 64%; Duval County, FL, home to Jacksonville, at 62%; Pinellas County, FL, home to St. Petersburg, at 61%.

The next largest price gaps were in Dallas County, TX, at 52%; Hillsborough County, FL, home to Tampa, at 50% ; Erie County, NY, home to Buffalo, at 49%: San Diego, at 49%; and both Essex County NJ, home to Newark, and Cuyahoga County, OH, home to Cleveland, at 41%.

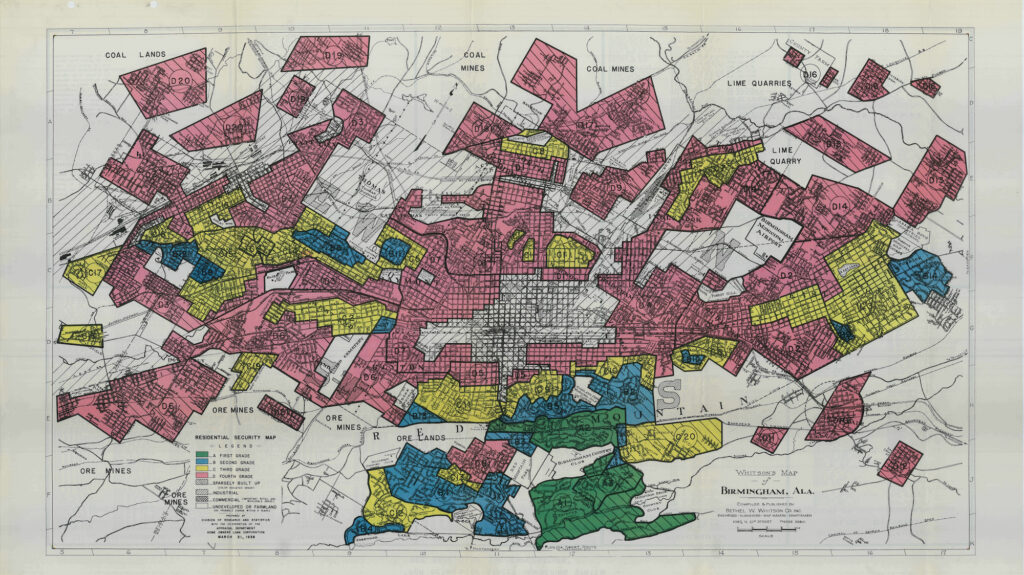

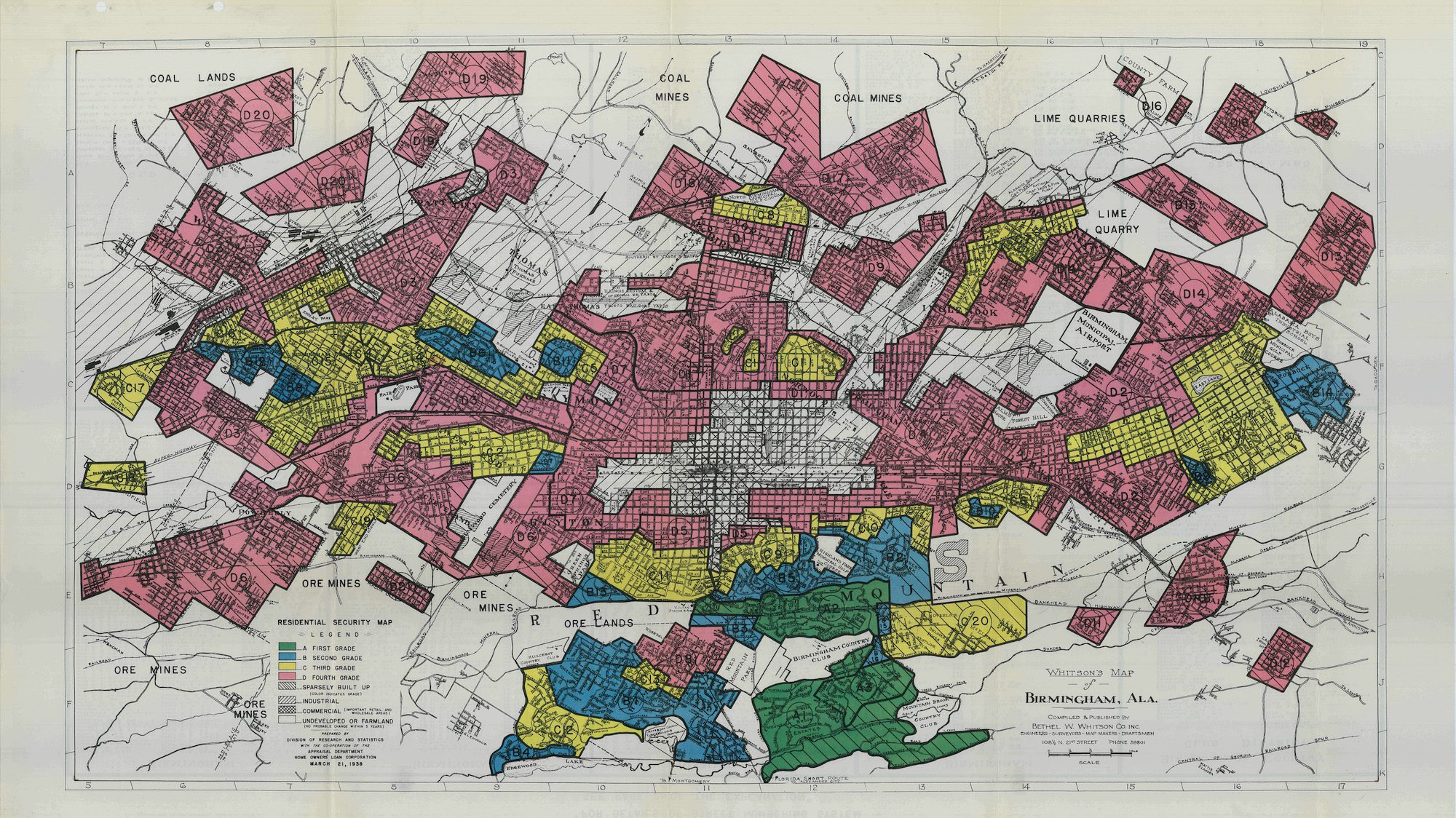

To come up with these findings, we compared historically white, non-redlined areas, originally graded as A and B neighborhoods, and compared them with formerly redlined communities, known at the time as C and D neighborhoods. We then figured out the average price difference between homes sold in redlined and non-redlined communities in 2019 in the 100 largest counties where both housing data and redlined maps were available. This narrowed our analysis to 55 counties.

Redlining got its name from the actual lines drawn on maps created by the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation, a federal government–sponsored agency, to identify areas where lenders believed it was riskier to loan money to home builders, buyers, and owners.

The realtor.com analysis used sales data from CoreLogic and maps from the University of Richmond’s Mapping Inequality project.

Neighborhoods were broken down into four color-coded groups by the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation. A communities, which were shaded in green, were considered the “Best” communities, where native-born white Americans lived. B neighborhoods were shaded in blue and considered “Still Desirable.” This is where many white immigrants lived.

Lenders were more hesitant, or simply refused, to lend in C, yellow areas thought of as “Definitely Declining,” and D, communities that were colored red and considered “Hazardous.” “Definitely Declining” areas had a higher immigrant population, and “Hazardous” ones were mostly inhabited by Black Americans.

“If the community [today] is being seen as having a particular racial makeup, there’s code words that may be used whether or not [it’s called] a bad community,” says Brown, also a real estate agent at Keller Williams Realty in Trussville, AL, a Birmingham suburb. And when homeowners in these formerly redlined communities sell their homes, they’re “going to make a lot less money off of it than someone in another community.”

Racial discrimination isn’t the only reason for lower home values

The Washington Post / Contributor/Getty Images

Discrimination isn’t the only reason why properties in formerly redlined areas were sold for less.

From the beginning, these communities have traditionally suffered from a lack of investment. Residents in these areas are more likely to be struggling financially, if the neighborhoods haven’t gentrified, and there are often higher concentrations of renters. They also may have higher crime rates, underperforming schools, and fewer amenities, which can range from grocery stories to access to quality public transit. Plus, the housing stock often simply isn’t as desirable.

All of this drives down home prices.

“Poor neighborhoods [often] don’t get the same police protection, sanitation, drainage, utility coverage,” says Troutt. “They’re the first to flood; they’re the last to see repairs.”

They also lack many of the businesses that home buyers want to have nearby.

“People are really frustrated,” says Atlanta-area real estate broker Amy McCoy, of My Hometown Realty Group. She sees that many of the nice stores and restaurants go into the predominantly white areas, while the Black communities get the dollar stores, distribution centers, and apartment complexes.

“It’s always been in the Black communities [that] we have the subprime type of lenders, such as the check cashing places. You just don’t have the Whole Foods. You don’t get the Trader Joe’s.”

Many of the homes in formerly redlined communities are smaller, and they’re usually not made with higher quality materials, such as stone and brick. Today, many are rentals owned by landlords who don’t live in the community, who are less incentivized to maintain them.

These communities are also more likely to be closer to major highways, slaughterhouses, refineries, and other things that can drive down home values, says Robert K. Nelson, director of the digital scholarship lab at the University of Richmond in Virginia. They may also have health hazards and higher temperatures.

“You’ve got to put a landfill someplace,” says Nelson. “That’s not going to go into well-to-do, white America.”

Many redlined communities have remained stigmatized

Another problem is the reputation of many of these formerly redlined areas hasn’t improved much over the decades. If an area was stigmatized in the 1960s as being unsafe, that perception is likely to continue into the 1980s and 2000s (with the exception of gentrification—more on that later). It’s not as likely to attract investors or homeowners who can afford to go elsewhere, particularly if crime rates are high and test scores at the local schools are low.

“It’s very hard to overcome that,” says Troutt.

At the same time, homeowners in these areas also may have higher property tax rates than homeowners in white communities, says Troutt. That may be in part because there are fewer homeowners to pay for the services needed by the entire community.

But they can also penalize residents who are more likely to earn less than their white peers.

In 2019, non-Hispanic white households had a median household income of $76,057, according to U.S. Census Bureau data. Black households made about 40% less, at a median $45,438 a year.

“Neighborhoods that were poor in the 1930s are more likely to be poor today,” says Richard Rothstein. He is the author of “The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America.”

The exceptions are areas that have been gentrified in recent years. There is no difference in prices between redlined and non-redlined communities in New York’s Kings County, better known as Brooklyn. That’s because the area has largely been gentrified, with popular concert venues, buzzy bars and restaurants, and newly built housing for young professionals.

Other formerly redlined areas seeing the effects of gentrification, according to the realtor.com analysis, are Hudson, NJ, where homes are worth 1% more than in non-redlined areas; Baltimore, up 5%; and Philadelphia, up 18%.

Why home prices in Birmingham’s formerly redlined communities are still depressed

Universal History Archive / Contributor/Getty Images

The charged racial history of Alabama’s Jefferson County, home to Birmingham, may help to explain why homes in formerly redlined communities sold for 74% less than those in non-redlined areas.

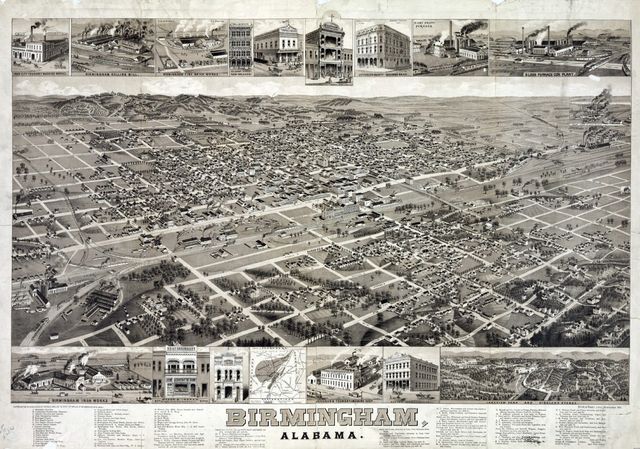

“Birmingham was founded after the Civil War. It was never intended to be [racially] integrated,” says history professor John Giggie. He is also the director of the Summersell Center for the Study of the South at the University of Alabama in Tuscaloosa. “Those redlining maps were simply codifying practices and policies in place since the city’s inception.”

Segregation may be illegal today, but Jefferson County remains largely divided along racial lines, says Barry McNealy. The lifelong Birmingham resident is the education program consultant for the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute and a local, high school history teacher.

“There are neighborhoods that are just as oppressed as they were in the 1950s and ’60s,” says McNealy. Homeowners may have a harder time selling homes in these areas and often get significantly less for them than similar homes in predominantly white areas. That continues to financially hurt residents of redlined communities.

“It’s like an attack on being a minority,” says McNealy.

He says there are plenty of changes underway to right some of these wrongs. They include things like the city providing homeownership counseling and support to help Black residents become homeowners. But changes don’t happen overnight.

“The Deep South in general and places like Birmingham are still grappling with the legacies of the past,” says Giggie. “What makes [Birmingham] so different is its history, so deeply tied to its racist origins.”

Data analysis by Nicolas Bedo

The post Redlining Was Banned Decades Ago, but Its Effects on Black Communities Can’t Be Erased appeared first on Real Estate News & Insights | realtor.com®.